How Rollups Work

A rollup is a blockchain that consists of a state transition function executed over some subset of data contained in another blockchain, the L1. Bridging to/from the L1 (by enshrining the rollup’s state transition in the L1) is implemented by non-sovereign rollups.

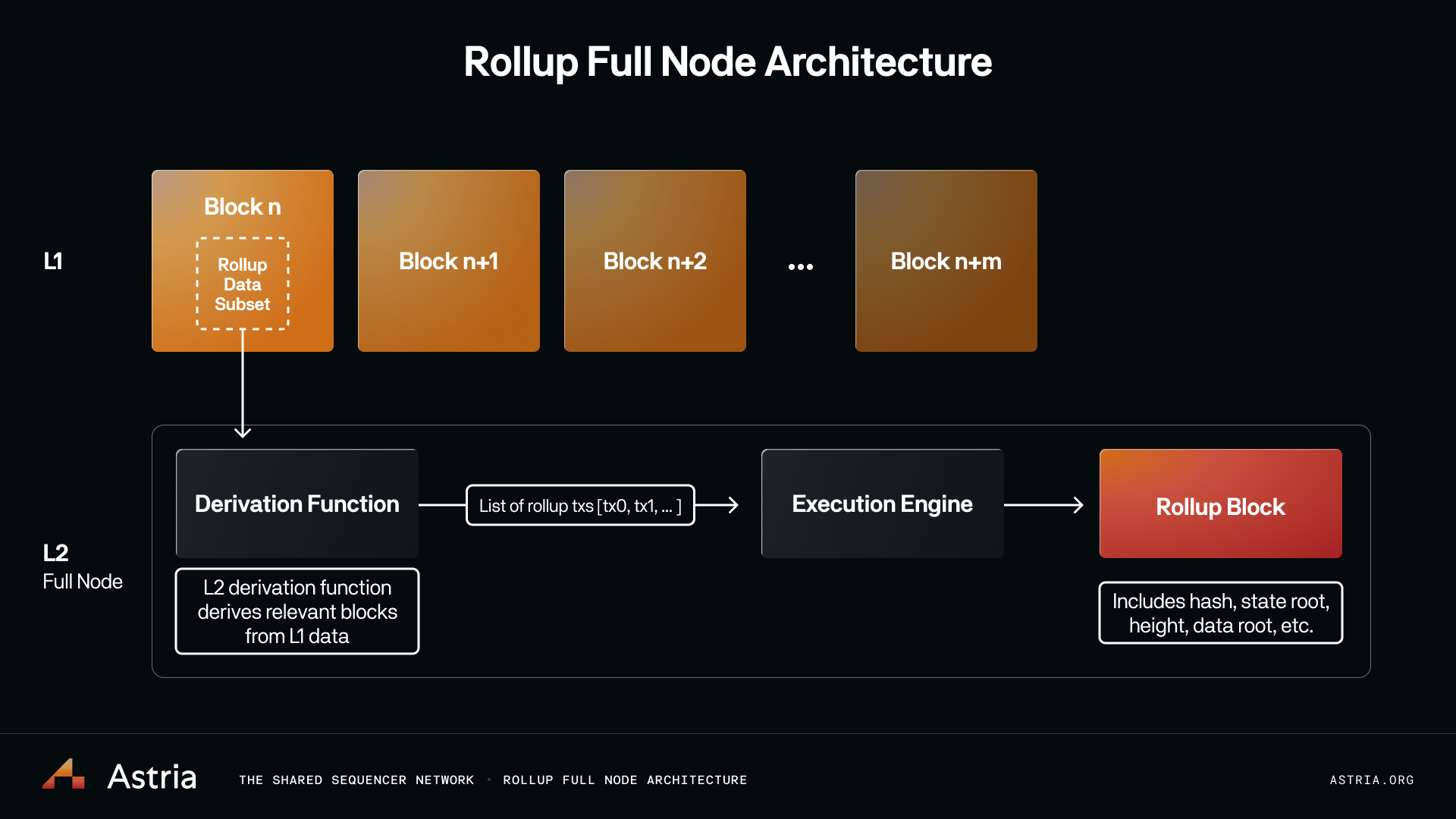

Rollup Full Node Architecture

A rollup needs to perform the following:

- read relevant subsets of data from the L1

- turn this data into rollup transactions

- execute these transactions to form a rollup block

The first two points are part of “rollup consensus” while the last is “rollup execution”.

The main component required for rollup consensus is an L1 derivation function, which derives the transactions for a rollup block deterministically from the data on the L1. This data generally looks like calldata or blob data posted to the chain and/or events emitted from a contract. This data is extracted and turned into rollup transactions.

After the set of rollup transactions for a block has been derived, they are passed to the rollup execution layer, which executes the transactions and updates the rollup state. After execution, a new rollup state root is created.

Unlike L1 nodes, rollup nodes do not necessarily need to form a p2p network and communicate with each other for consensus. The chain’s consensus is provided by the L1, and all (properly-functioning) rollup nodes will deterministically derive the same state given the same L1 state.

However, rollup nodes may still wish to form a p2p network for two reasons: fast confirmations, which can be received from the sequencer, or for rollup light nodes.

Rollup Sequencers

In the above section, we discussed how a rollup derives its transactions, but how does the rollup data end up on L1?

A simple solution is to have users post their rollup transactions to the L1 directly. However, this is not ideal because there is not as much of an economic benefit (users have to pay for L1 inclusion, plus L2 execution) for them to do so. As well, users need to wait for L1 blocks to know if their transaction was included.

A more cost- and time-effective solution is to use a sequencer. Rollup sequencers are akin to block producers on L1. They have the privilege of determining ordering and inclusion for rollup blocks. The sequencer collects a set of rollup transactions, batches them, optionally compresses them, and posts them to L1. Compression has the benefit of reducing the L1 inclusion cost for each rollup transaction. Sequencers also provide “pre-confirmations” or “fast confirmations”, meaning the sequencer can provide a commitment to the user that their transaction will end up in a specific rollup block before the corresponding L1 block has actually been published.

Sequencers to date have been implemented as a centralized service, generally run by rollup teams themselves. This means there is one party responsible for rollup transaction ordering and inclusion, leading to a monopoly on MEV extraction and the potential for transaction censorship. While there is always the “escape hatch” by which users post their rollup transactions directly to the L1 for inclusion on the rollup, this is a poor UX alternative.

Decentralized Sequencers

A decentralized sequencer network is an alternative to the centralized service, where multiple sequencer nodes each have the ability to propose a batch of rollup transactions.

The flow would then look like:

- a proposer proposes some transaction batch, or commitment to some transaction batch the network reaches consensus over this batch

- the transaction batch data is made available to rollup nodes

A simple solution is to have a permissioned set, where only batches signed by a key from the chosen set are allowed to be derived into rollup blocks. To make this permissionless, we need to allow anyone to join the sequencer node set - eg. through proof-of-stake. By putting up some stake, anyone can join the sequencer network as a consensus node, and have the privilege of proposing transaction batches.

There are a few options regarding the asset(s) used as stake on the sequencer network. The first is to create a native asset on the sequencer network to be used for staking, as well as for transaction fees. The second is to use the asset of an underlying data availability layer for staking and transaction fees.

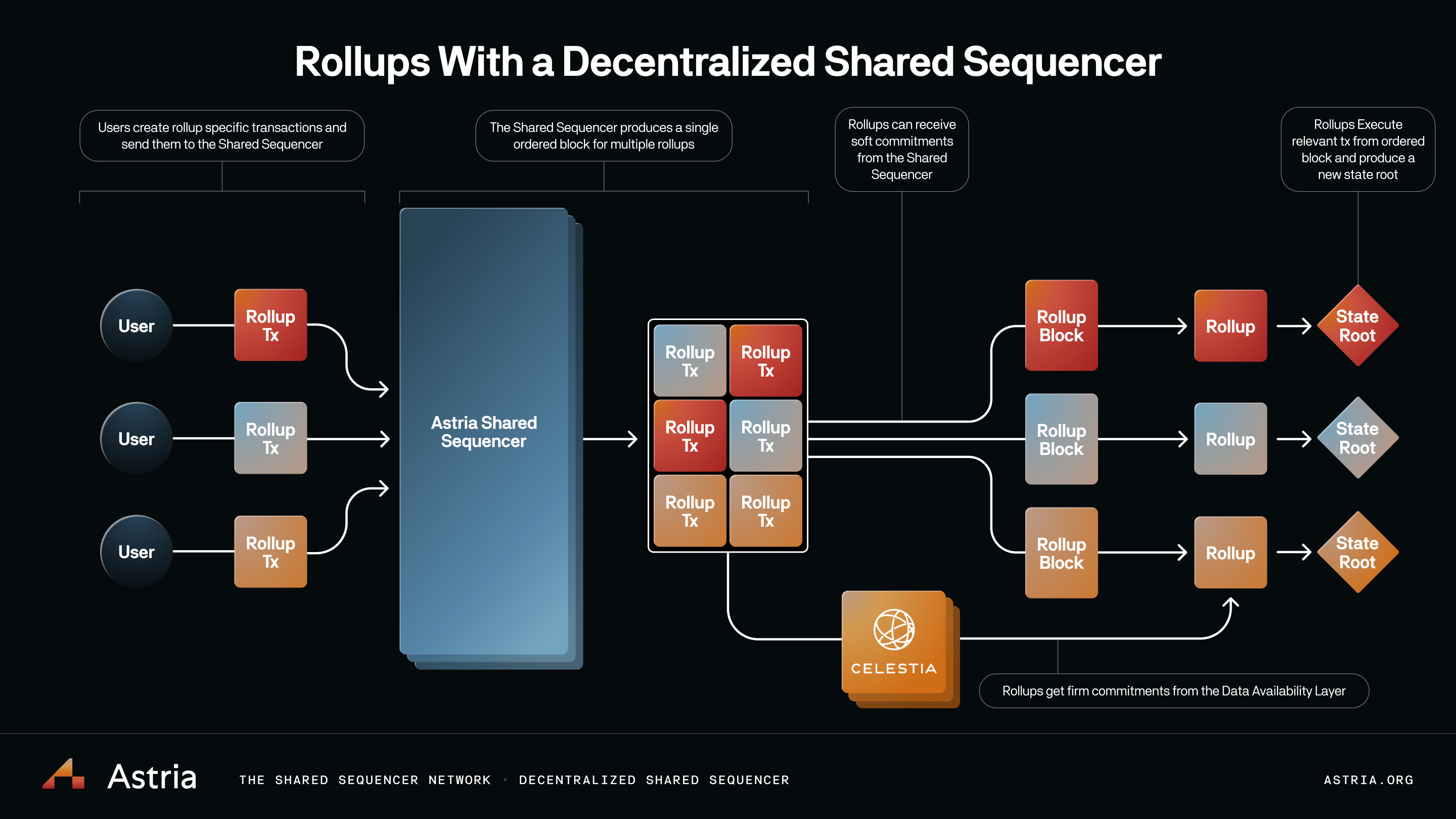

Sequencing Layer

Currently, sequencers are implemented for one specific rollup. Instead of this, we can have a sequencer batch transactions for many rollups. With data compression, this allows for greater cost savings when posting data to L1. A sequencer network that is decentralized and shared incentivizes actors from multiple rollup ecosystems to potentially act as validators on the sequencer network.

Current sequencer implementations generally execute the transactions that it sequences as well. By allowing the sequencer to sequence many rollups, it can either execute the transactions for each rollup it sequences for, or have it not execute any transactions at all, and remain ignorant of the rollup state machines it’s sequencing for (known as lazy sequencing).

The downside to executing the transactions for each rollup is that it’s much more difficult to add new rollups to the sequencing layer, as the sequencer needs to be forked and made aware of a new state machine. Additionally, as the state of the rollups grows, the sequencer execution time gets slower and slower (the same way state bloat affects L1s), but it’s potentially even worse over time since many states are involved.

The better solution is the second, where the sequencing layer’s function is reduced to only sequencing and not executing. In this model, the sequencing layer batches and orders generic transaction data, where the data is tagged with the rollup it’s destined for, and only after the sequencer commits to the batch is the data executed by rollup nodes.

Rollup light nodes

Rollup light nodes, like normal L1 light nodes, follow the consensus of the main chain and verify and sync its headers, without executing the full transaction data of the chain. A rollup light node needs to do a few more things to verify headers than an L1 light node.

A rollup light node needs to:

- implement an L1 consensus light client

- implement an L2 consensus light client

- ensure that the transaction data for each L2 block was published

A light node of a rollup that uses a sequencing layer needs to verify the consensus of the sequencer chain, as the sequencer acts as the equivalent of the L1 - i.e. it’s where transaction inclusion and ordering is finalized. It needs to follow the headers and verify consensus of the sequencer chain. Since light nodes don’t store the blockchain state, to verify if a rollup transaction was included in some rollup block X, the light node first needs a Merkle proof that the rollup transaction was included in the transactions/data root of some sequencer chain header. Then, if it follows that rollup block X was derived from sequencer block Y (using the rollup derivation function), it knows that the transaction should be included in rollup block X. The light node also needs to check that the block data was published, which it can do via data availability sampling (for example, when using Celestia).